Thermal stress in swine

Thermal stress is a common problem in animal production. Genetic selection for thermal resilience is not as simple as it was for productivity, and these 2 traits may even be negatively correlated.

High stocking densities, common in most high-yield farms, obviously has a strong effect in increasing animal temperature. Swine are at a disadvantage in relation to other livestock, as they have relatively small lungs (air exchange reduces temperature) and do not have sweat glands (thus the need to lay flat sideways on the ground to exchange temperature). Furthermore, with the current increase rate in global temperatures, it is possible that the problem may expand to previously unaffected areas (albeit also bringing some colder areas into thermal comfort).

The consequences of heat stress for swine are numerous. The most obvious, and most important consequence of heat stress affects the welfare of the animal.

Animals vocalise in greater intensity and with distinct stress patterns. As animals tend to lay down for cooling, there is also reduced feed and higher water consumption. Feeding is itself thermogenic as calories are being effectively used for growing. This stress response with reduced feeding leads to impairment of gastrointestinal health. The changed feeding pattern impacts the microbial population within the intestine. In turn, the altered microbiota affects the development of immune cells in the intestinal walls, and thus animals are exposed to more infections – which are also thermogenic for the host (e.g., fever).

What can be done?

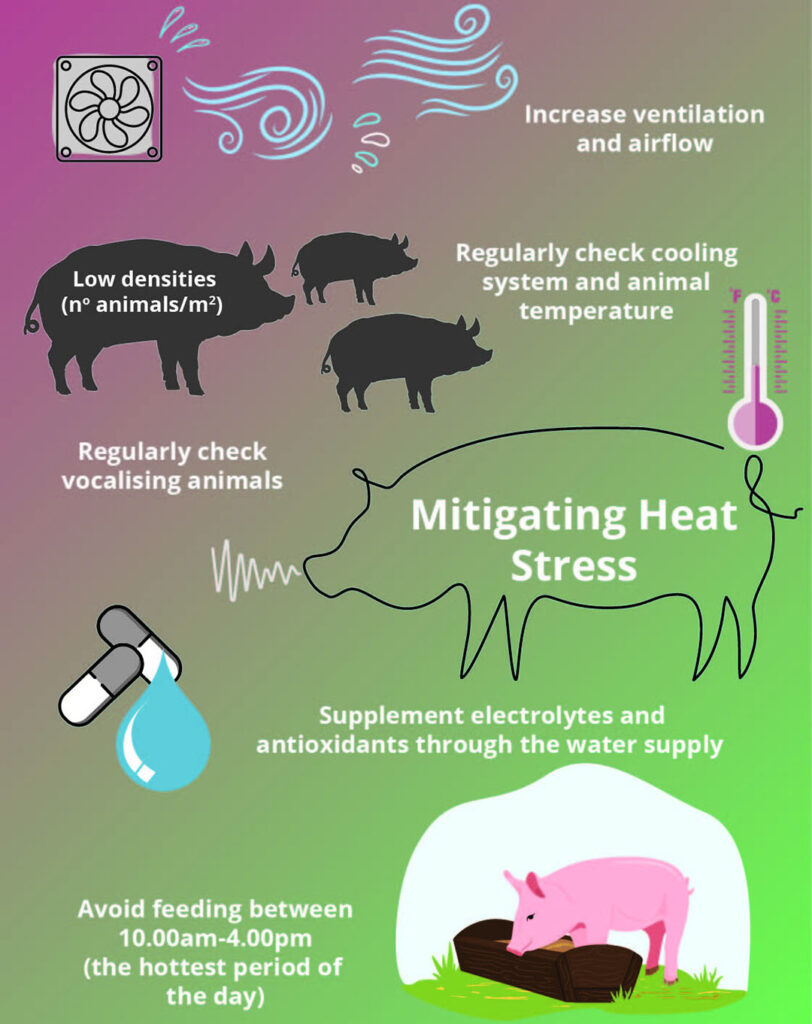

The most efficient methods for thermal control in swine rearing are environmental modifications. There are many great reviews on the best physical temperature control measures. The most widely accepted methods of physical temperature control are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – These are some of the most important measures for swine health during periods of eat. Everything that reduces overall animal stress and that reduces metabolic demands – while maintaining health and welfare –will be useful.

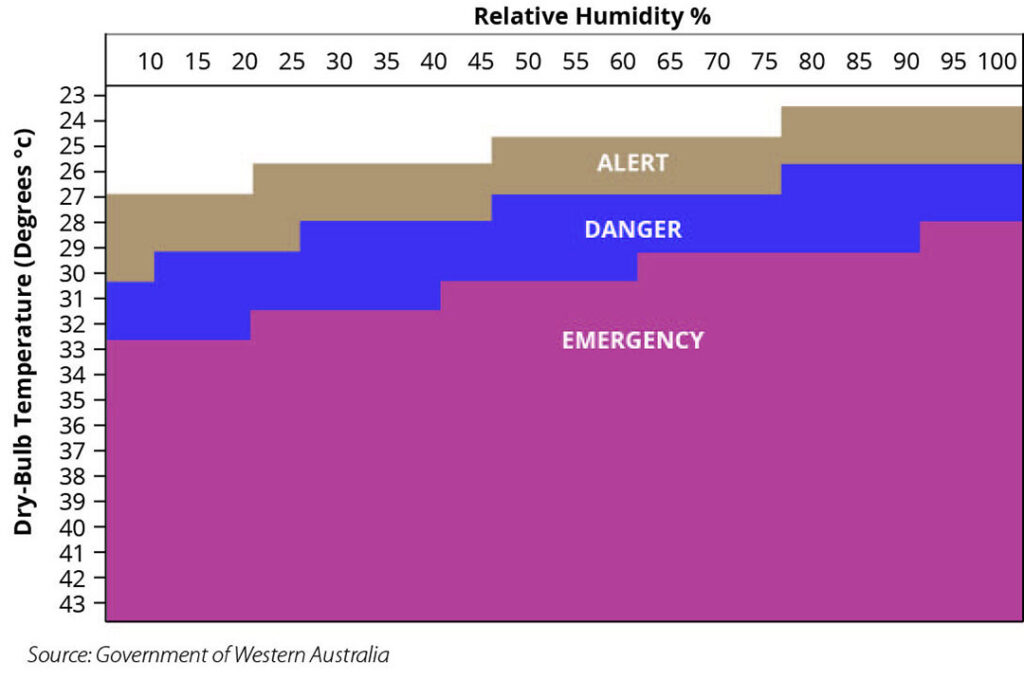

In the real world, it is often difficult to implement or maintain some of the methods in Figure 1. Also, in many cases of thermal stress it is necessary to combine several measures to effectively control the pathogenic consequences (Figure 2). This article will expand on the nutritional and immune measures that can be taken against heat stress for swine.

Figure 2 – Temperature and humidity stress index for growing-finishing swine. In conditions of high humidity, animals have lower temperature tolerance.

Nutritional measures

To maintain levels of productivity and welfare through a phase of heat stress, producers should supplement electrolytes and antioxidants through the water supply. For example, the study of Parraguez et al. indicates that “supplementation of pigs throughout gestation with herbal antioxidants significantly improves reproductive efficiency, litter characteristics, and piglet performance during the birth-weaning period”.

When feasible, diet composition should be changed. This is only possible when heat waves are predictable (e.g. summer in tropical and subtropical countries). Diet should have high energy density and low fibre so that intestinal fermentation is reduced, and therefore heat production within the animal is also limited.

Immune measures

Immunity has an impact on thermal stress, and vice-versa. Fighting infections is highly thermogenic. Fever has been cited as one immune mechanism that can increase body temperature. Immunity is also highly demanding in energy and protein, and satisfying these demands goes against the nutritional measures cited above. But there are many other mechanisms, such as inflammation that can also induce vasodilation in internal organs, reducing blood flow to the skin, where heat is lost. As mentioned, heat stress leads to poor intestinal health, thus favouring infections. Lymphocyte cell cycle is further damaged during heat stress, thus decreasing immune defences. In sum, heat stress worsens the outcomes of infection and also the other way around, in a loop of negative self-reinforcement. Antioxidants are beneficial in this context, as they are able to counteract the oxidative nature of inflammation and of other cell imbalances induced by heat.

Pro and prebiotics

Impoverishment of intestinal immunity and barrier function are among the main reasons for increased susceptibility to infection during heat stress. Not surprisingly, probiotic and prebiotic administration has positive effects during heat stress in swine. These supplements – and others, e.g., with antinflammatory capacity – seem to revert the bacterial dysbiosis in the gastrointestinal tract and restore the function of the intestinal barrier and of mucosal immune cells.

Mucosal vaccination

Intestinal barrier function and immune responses can be further enhanced by mucosal vaccination. This form of immunisation often produces IgA, which is regarded as an “antinflammatory immunoglobulin”. IgA acts by three mechanisms in this regard:

1) IgA blocks pathogens even before they contact host cells. Circulatory immunoglobulins are only able to bind to pathogens after tissue invasion, but IgA is located in the mucosal lumen, thus blocking pathogen binding to epithelial cells of the intestines, lung etc.

2) IgA is non-complement binding. The complement is an inflammatory immune effector that is activated by several antibody isotypes, but not by IgA .

3) IgA binds to and maintains a healthy microbiota. Commensal bacteria are positively selected by IgA within the mucosae, therefore creating another barrier against infections.

Unfortunately, IgA production is not induced by parenteral (injectable) vaccines, in most cases. Therefore, special mucosal vaccines are needed for this purpose. These are specially designed to induce protection against the very mucosal pathogens that are prone to invade during heat stress. Vaccination mucosal or injectable, of course, has always a downside, which is itself inducing inflammation. This is a prerequisite for establishment of proper vaccine immunity, and there is no efficacious vaccine free of this adverse effect. Therefore, vaccine formulations must be precise, in dose of antigen and adjuvant choice – when considering autogenous vaccines. For on-label vaccines, dosage and delivery conditions cannot be missed. Wrong vaccine dosages carry the risk of not immunising the herd (low dosing or dose lost to biofilm adhesion, to poor spraying practice etc) or of inducing excessive inflammation (excessive dosing).

Multifaceted strategy approach

Strategies that induce mucosal immunity maturation, be it nutritional or via vaccination, should be considered during states of temperature imbalances in swine production. Interventions that increase pulmonary and intestinal health should be sought. Especially, it must be noted that no single protocol will be valid to all farms. Test avidly on smaller groups of animals and measure animal health and productivity parameters before any intervention is implemented farm- or company-wide. Always ask for samples of products that can be tested from your supplier, this is what free samples are for, to be validated in your reality.

References are available on request.

Beheer

Beheer

WP Admin

WP Admin  Bewerk bericht

Bewerk bericht