New paradigms for disease prevention

For a long time, biosecurity belonged to the realm of protocols, paperwork and good intentions. It worked when everything was put to practice – but loopholes were plentiful. Nowadays, subjective measures can be complemented by novel technologies to enhance biosecurity levels.

Pig production is currently going through unknown territories because of 2 new significant factors, African Swine Fever (ASF) and Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). Both phenomena, besides already existing diseases, are affecting competitiveness in terms of efficiency and quality of production and are directly related to biosecurity control. Therefore, better control of biosecurity is becoming more important than ever.

Biosecurity data

Biosecurity is known as the implementation of measures to reduce the risk of introduction and spread of pathogens, preventing the transmission of diseases, thus improving health and reducing the need for antimicrobials. Moreover, most diseases harm the well-being of the animals and consequently their productivity. Hence, higher levels of biosecurity will have a positive effect on the economy of the farmer. When performing biosecurity audits in Western/Eastern Europe as well as Asia, pig producers frequently reply in a fairly similar way when mistakes are found: “We always do well, but just today…” and this is one of the crucial points, the exceptions. In general, farm staff members know the theory or the working principles they should follow – they just don’t comply in every case. Here are some examples:

- Responsibilities not assigned to anyone. Despite comprehensive written protocols, they might not be put in practice because responsibilities are not assigned or people have not been properly trained to do so;

- Mixing of personnel in common areas, like a canteen, without changing boots or clothes;

- Showering partially because ‘you are not going to take a shower four times a day’;

- ’I am special’. Owners, managers or maintenance staff feel sometimes that general rules do not apply to them;

- Public and private roads are used with no preventive measures at all;

- ’Creativity’ in complying with the rules. “I only take a shower when I arrive in the morning.”

Creating a new type of data

Since biosecurity affects all the processes that take place on a farm, it is essential to have a standardised evaluation method with complementary parts: subjective and objective control. Both improve each other and lead to a better and more robust and efficient overall biosecurity control (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Schematic of biosecurity control (human + digital).

Subjective control

This type of control consists of the classical approach based on data collection from farms, surveys and checklists from the farm, with some improvements based on experience. PigChamp Pro Europa is a consultancy firm for pork producers. When a farmer wishes to improve biosecurity, the control is based on 4 steps:

- Information collection. That includes at the very least a detailed farm map, health status, gilt acclimatisation programme and general biosecurity protocols;

- Surveys. PigChamp uses the Biocheck survey, which evaluates the different factors affecting general on-farm biosecurity, further elaborated with some questions added from our own experience to address ‘in more detail’ specific areas. Biocheck allows to benchmark results as well with other farms globally. These two firsts steps provide a good understanding of the current situation on the farm but needs to be re-checked with a farm visit.

- Farm visit. A full in-depth visit to the facilities, checking information received, talking to farm staff and farm managers is of great help to ensure what the real situation is on-farm. Very often, inconsistencies or reality vs theory are noticed when being on-site. That usually takes one or two days.

- Solutions based on the analysis performed. All information collected must be processed, analysed and lead to an action plan that is carefully presented to the company, the farm manager and the farm staff, including short, medium- and long-term actions.

The limitations of this are related to the subjectivity of data reported, sometimes even with the best will, but answers could be more related to guesses rather than facts, and they are not always verifiable. A farm visit would typically generate an image of what is happening at that moment only, which may match totally or only partially with reality. Finally, a follow-up is mostly based on the repetition of that process, rather than in getting objective information about the recommendations agreed. Altogether, biosecurity audits appear to be the best possible solution for now with a clear margin of improvement.

Objective control

Objective control is based on data, generally obtained by digital technologies. That approach complements the drawbacks of the subjective method mainly with regard to two of the unknown aspects: disease entry (external biosecurity, visitor control) and internal disease spread (internal biosecurity, farm staff movements).

External biosecurity

Usually, there are few data available addressing external biosecurity. There are 2 options to address that gap:

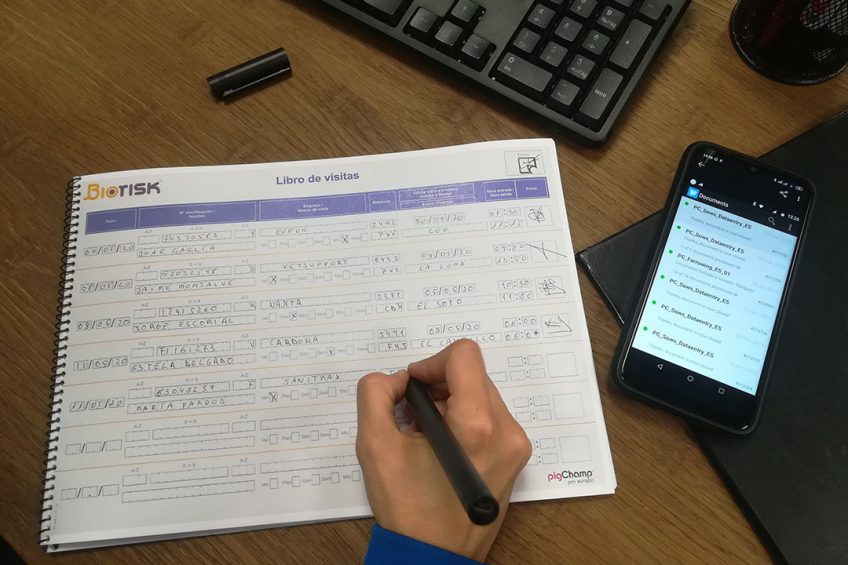

- An electronic visitors’ book. Most farms have a visitors’ book where each visitor records his/her data and signs. In practice, the use and benefits of this procedure are minimal, to check when a particular person visited the farm can be quiet time-consuming (as you would have to manually go through the logs) and it has little further value. A simple, easy-to-use visitors’ book based on ordinary paper, plus a digital pen and cheap smartphone is easy for most farm users since it is the same writing routine they use, but data can be instantly uploaded to the internet and transformed into useful information. It is a low-cost and easy solution (Figure 2).

- An access control system. This type of system is more sophisticated and is usually better for larger complexes including different types of farms and facilities. It is based on a system that has a predefined database of users which allows visitors to enter depending on the place they previously visited or other risk factors (e.g. nowadays the risk or positiveness to Covid-19). The system can generate instant alerts, easily monitor the compliance to company standards, it can improve the behaviour of visitors and favours later audits based on objective data.

Figure 2 – The system generates interactive dashboards and charts for real-time biosecurity control.

Internal biosecurity

In the case of internal biosecurity, the objective is to prevent the disease from spreading in the farm once the pathogen is there. The approach is mostly focused on economic diseases like PRRS, but could be applied to anything. A new digital internal biosecurity system (Biorisk) is based on 2 on-farm hardware pieces, including beacons and readers. Each farm worker is given small bluetooth transmitters called ‘beacons’. They are required to wear those whilst being on-farm. Readers are installed and fixed at every access point of every barn, including lockers and showers. Those devices can detect beacon signals by proximity. Whenever a beacon is within a device’s detection range, it registers the beacon identity as well as the detection time and uploads the record to a database.

Data collection and processing records from readers are then sent to the cloud and processed, so the farm workers’ movements and routes are logged. Each movement represents a route made by a farm worker from a starting point to the end destination. Thus, the system allows the real-time monitoring of the farm staff movement patterns and their risk of spreading diseases within the farm.

With the system it has been possible to control and eradicate diseases (PRRS) and improve operational excellence by better understanding human behaviour. Recent preliminary work (Arruda et al., 2019, unpublished) from collaborators at the Ohio State University showed an association between movement type and production efficiency using US farms. In the study, a five-hour increase in time spent in rooms by the manager was associated with an increase in one weaned piglet for every 10 litters.

In a second farm, an increase in time spent working in the farrowing rooms of about 2 hours per worker per week tended to increase the number of weaned piglets by 1 piglet for every 4 litters. Those findings could be related to an increase in pig care, which would likely lead to a higher number of weaned animals. Having control of this at a glance helps to ensure that operations are being performed as expected and make easier early personalised corrections.

Digital biosecurity and human control

Ensuring high biosecurity standards, to keep farms free of disease, can be performed easily by combining human control with digital systems. Those systems also promote operational excellence since a farm’s tasks are objectively supervised. They favour remote monitoring, avoiding risks of entry and making the work of veterinarians and managers more efficient. The combination of good protocols, human expertise and digital technologies will define a new paradigm in the control of biosecurity in swine farms in the upcoming years.

For more information mail: inmaculada.diaz@pigchamp-pro.com.

Co-authors: Cristina Escudero, DVM; María Aparicio, DVM, and Dr Carlos Piñeiro, DVM, PigChamp Pro Europa

Beheer

Beheer

WP Admin

WP Admin  Bewerk bericht

Bewerk bericht