Johne’s disease – new advances, new era

A study on herd elimination of the disease is moving forward in the province of Alberta, Canada. There is also news on a vaccine development strategy that promises real results for the first time in Johne’s disease history.

Johne’s disease (JD) continues to be a significant infectious disease affecting dairy and beef farmers in Canada and beyond. “In Western Canada, approximately 70% of dairy herds are infected,” notes Dr Herman Barkema, professor of epidemiology of infectious diseases at the University of Calgary in Alberta, the Natural Science & Engineering Research Council (NSERC) ‘Industrial Research Chair in Infectious Diseases Research’ and a guest professor in the department of obstetrics at Ghent University in Belgium.

Profile

Dr Herman Barkema, Professor Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases, University of Calgary. Photo: Dr Barkema

Controlling Johne’s disease

There are many barriers to controlling JD, primary among them is that the infectious agent, Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis (MAP) bacteria, most often infects cows without causing clear clinical symptoms. Dr Barkema explains however, that whilst dairy cattle may not show severe symptoms for years, both calf growth and later milk production are impaired because of lowered rates of nutrient uptake due to thickening of the gut. Treatment would be costly and take months, involving a combination of antibiotics due to antibiotic resistance issues. In addition, re-infection would be highly likely since MAP is a persistent survivor in the farm environment, spread through manure and water, colostrum and milk. He adds that testing for the infection has not been effective because antibodies develop only later in the infection. “The focus has therefore been on prevention of infection of calves through farm-level management practices, particularly focusing on hygiene and trying not to purchase potentially infected animals.”

Johne’s Disease Initiative

To help control the disease, a few years ago the Alberta Johne’s Disease Initiative was launched. It involves a farm risk assessment and recommended control strategies. However, research with some Alberta dairy farmers concerning implementation of on-farm JD prevention and control has shown that “often JD was not perceived as a problem in the herd and generally farmers did not regard JD control as a ‘hot topic’ in communications with their herd veterinarian and other farmers.”

Still, Dr Barkema is hopeful. He explains that due to past research that has been enthusiastically supported by the dairy industry in Alberta, Western Canada and nationally, “our knowledge of JD has progressed quite a bit in the last decade and we think that we are now ready to control JD on a dairy farm.” Indeed, Barkema and colleagues recently received funding from the Agriculture Funding Consortium and through NSERC to determine whether JD can be eradicated in a dairy herd. “This study will be carried out on ten Alberta dairy farms,” he reports. “In addition to other known risk factors, we will also address calf-to-calf transmission and detection of the infection in calves, and we will evaluate some new diagnostic tests.”

Barkema is also involved in a Genome Canada-supported project lead by researchers at the University of British Columbia, the University of Guelph in Ontario and VIDO-InterVac (Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization- International Vaccine Centre at the University of Saskatchewan) to develop a JD vaccine.

…our knowledge of JD has progressed quite a bit in the last decade and we think that we are now ready to control JD on a dairy farm.

New vaccine development strategy

The history of JD vaccine development has not proven fruitful, notes Dr Philip Griebel, who is part of VIDO’s JD vaccine development team, the Canada Research Chair in Neonatal Mucosal Immunology and a professor at the University of Saskatchewan. He notes that there have been many past international attempts to identify JD vaccine candidates but all have failed.

In short, the VIDO team is using a vaccine development and screening strategy based on a method first developed at VIDO for sheep two decades ago. But first, let’s go over how a vaccine for MAP bacteria must function. These pathogens secrete antigen proteins which cause a response in a cow’s immune system. A total of 163 antigens have been identified from the three main MAP strains and they are now being screened to determine which are most important in causing a response (are therefore most suitable in a vaccine). At this point, the VIDO team is screening fewer than 90 candidates in groups of five. Testing the vaccines however, is not a simple matter of injecting young cows with candidate proteins, infecting them with JD and then determining (through blood sample analysis) if immunity has been generated. As Griebel explains, the immune response for JD in a cow’s blood does not accurately reflect the level of immunity nor the level of MAP infection in the intestine.

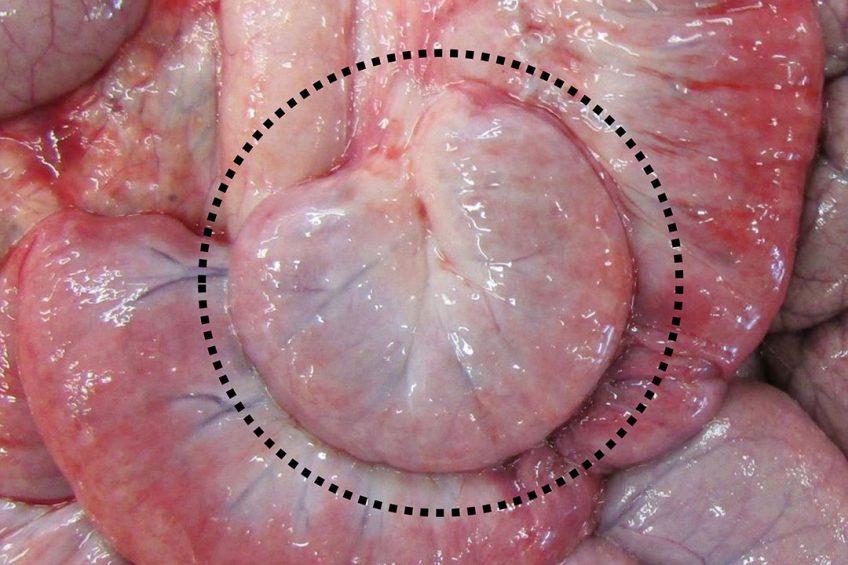

The VIDO team is therefore using a model focussed on the digestive tract. After a young ‘study calf’ has been given a vaccine candidate, the animal undergoes a surgical procedure. “We isolate a segment of the calf’s intestine from the rest of the intestine while ensuring it stays functional, with proper blood flow,” Griebel explains. “We then inject the MAP into the lumen of the isolated segment, reproducing the natural route of infection when MAP is ingested by a young calf. Then we can collect the targeted site of infection one or more months later to measure the level of MAP infection in both the intestinal tissue and the contents of the intestine. Quantifying bacterial infection at these two sites provides an indication of how well infection persists in the intestinal tissue and also reveals how much MAP may be shed in the manure of these calves. Reducing both MAP infection and bacterial shedding in faeces provide critical measures of vaccine efficacy.”

Over the last few years as the surgical procedure has been perfected, the team has also ensured that the MAP isolate being used results in a persistent infection; Griebel says previous research often used ‘lab’ strains that don’t survive well in calf intestinal tissue.

Looking forward

Having an effective and quantitative MAP infection model for young calves, the target age for vaccination, means in Dr Griebel’s view, that “we are now in a position to really make progress in narrowing down the vaccine candidates.” He explains that in the long term, to develop a commercial vaccine, pharmaceutical companies will need to test the most promising vaccine candidates in young calves subjected to oral MAP infection and then monitor MAP shedding over a 2 to 3 year period.

“A JD vaccine would be designed to have efficacy for years, and adjuvants (immune-stimulating compounds) can aid in achieving this longer duration of immunity,” says Dr Griebel. However, he adds that cows intended to live for several years will require revaccination. The commercial vaccine must also not cause an injection site reaction nor induce positive reactions with bovine tuberculosis tests, which has happened with JD vaccines in the past. And for maximum efficacy, a JD vaccine will need to be used in concert with appropriate herd management practices.

While this research problem is a very difficult one, its ‘that’ difficulty which excites Dr Griebel.

“Many scientists have spent millions of dollars on JD vaccine development, and many candidates have been tried but failed,” he says. “It’s rather arrogant for anyone to think they have solved this vaccine challenge, but we feel we have finally found a way during the last 3 years to screen candidates effectively, largely due to the efforts of Dr Antonio Facciuolo. We have the expertise now to identify effective vaccine candidates and we are feeling quite confident about our future results.”

Beheer

Beheer

WP Admin

WP Admin  Bewerk bericht

Bewerk bericht