Quarterly update: Global pork market is in a phoney war

The outbreak of war in Ukraine has been unforeseen, yet its impact is likely to be felt in the pig industry all around the world. In his quarterly update, pig market analyst Dr John Strak observes a trend towards higher pig prices, but also higher costs.

I ended my last piece for this column in January with the words, “The data, in my view, are positive for pig prices but there are external variables that we cannot measure or predict that can swing the market one way or the other.”

Well, that bit about “external variables” might yet be the understatement of the year. I also wrote in that column that I thought the year ahead looked like a glass half full and I was expecting pig prices to be relatively high throughout the year. Is that still the case? I will discuss the key components of the global market of pigmeat using several charts and tables and then try to summarise where that market might be heading in a post-Covid, post-ASF world that now has to deal with a war between Ukraine and Russia.

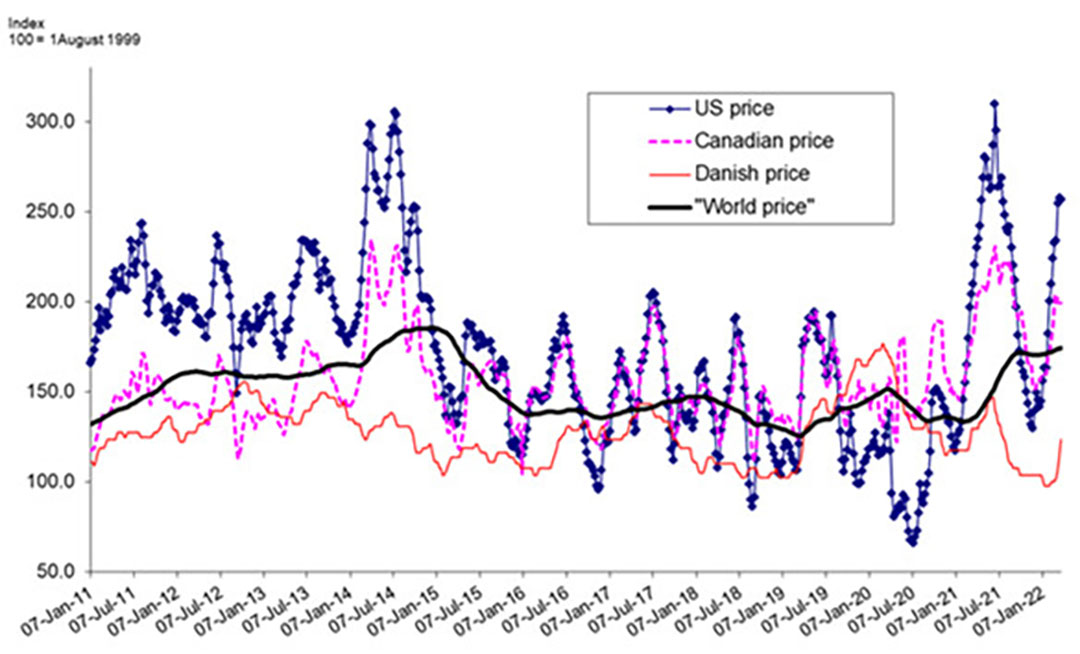

Figure 1 – Global pig price cycle: January 2011-March 2022.

Upward phase for the pig cycle

In summary, the global pig price cycle has turned up and Figure 1 illustrates this. The fundamentals point to an upward phase for the cycle this year with supplies and market hogs in decline in the major exporters’ herds. The global pig price index may now be back to acting as a leading indicator. Albeit for the wrong reasons, Covid-19 is off the front pages and African Swine Fever (ASF) seems to be just a minor irritation rather than a big news story.

However, either of both of these viruses could find themselves back on the front pages quite easily so caution is needed in business planning. As I noted last month, the signals from the underlying drivers of supply suggest that pig and pork supplies will be relatively tight in 2022 and, unless demand falls, this implies higher pig prices. This last sentence needs more consideration.

War: Effects of pig producers’ costs

The war in Ukraine has important effects on producers’ costs – we cannot discount a general collapse in producer confidence and/or in consumer incomes and demand. But these impacts have yet to show through in producer cost functions and consumer prices. We are, in effect, in a phoney war. The energy price hikes that are being experienced across the world will cut consumer incomes and economic growth later this year. Even China is not immune to this.

And how high will grain and feed prices go as shortages of fertilisers, grains and oilseeds hit livestock producers’ costs? Will retailers and foodservice providers sit out the “adjustment” as farmers and consumers find a new equilibrium for their relative supply and demand functions? Let’s review the data and then return to this question about market adjustment.

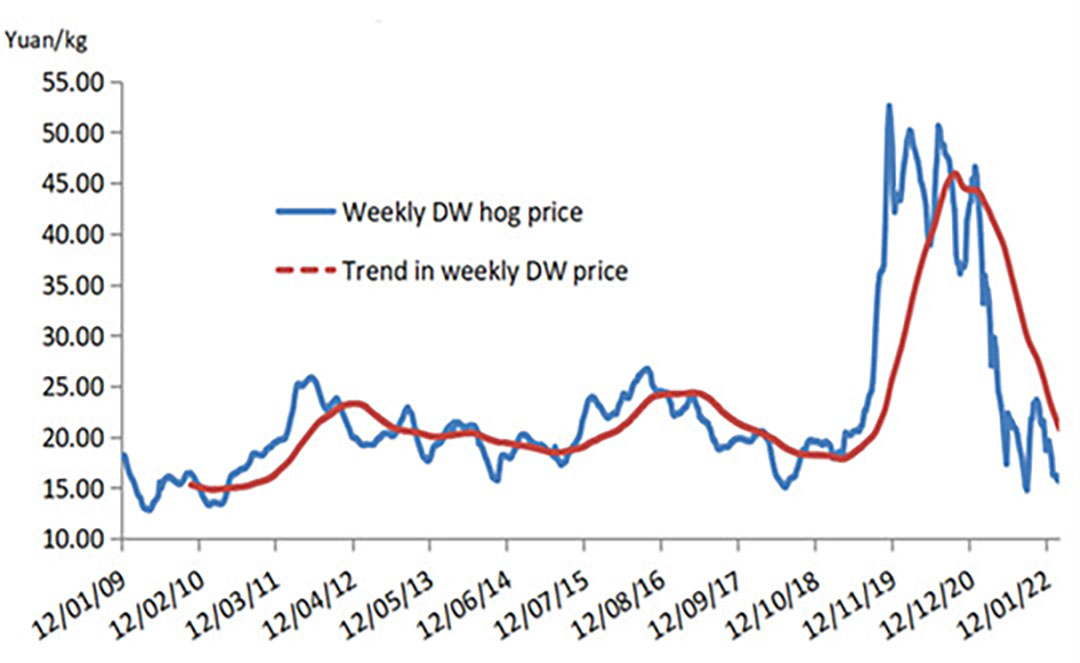

Figure 2 – Chinese hog price, 2009-March 2022 (dw, weekly).

Pig prices in China

Figure 2 presents a view of how Chinese pig prices have behaved and where they are now. There have been wild swings in supply and farmers’ prices, initiated by ASF-linked shortages. Chinese government purchases to maintain prices have occurred off and on for the last 12 months but hog prices in China are, effectively, on the floor and are well below production costs (and that is before the latest hike in costs that the situation in Ukraine has caused). It remains to be seen how large the contraction in the national herd in China will be as a result of these low prices but it should now be evident to the Chinese state that the country’s pig farmers have a keen interest in seeing hostilities end in Ukraine.

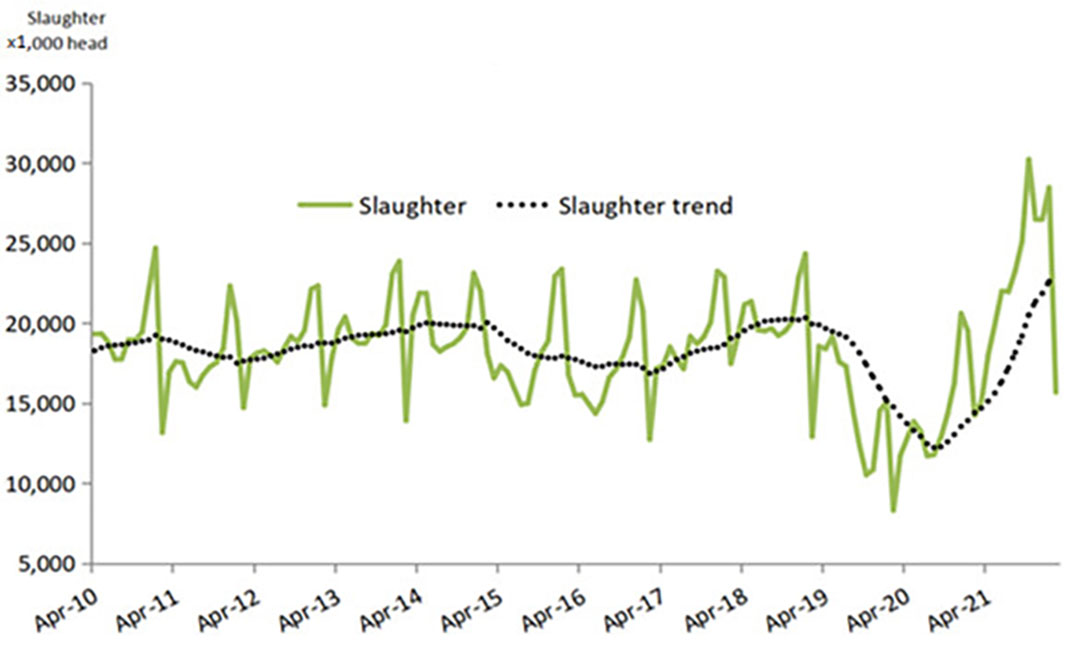

Figure 3 – Chinese hog slaughter, April 2010-February 2022.

Slaughter levels for Chinese pigs apparently peaked in late 2021 and early 2022 and the latest data in Figure 3 show a fall in kill numbers since the turn of the year. In parallel with these developments the level of pigmeat imports and the growth of foreign-sourced pigmeat shipped into China have declined sharply in 2021/22.

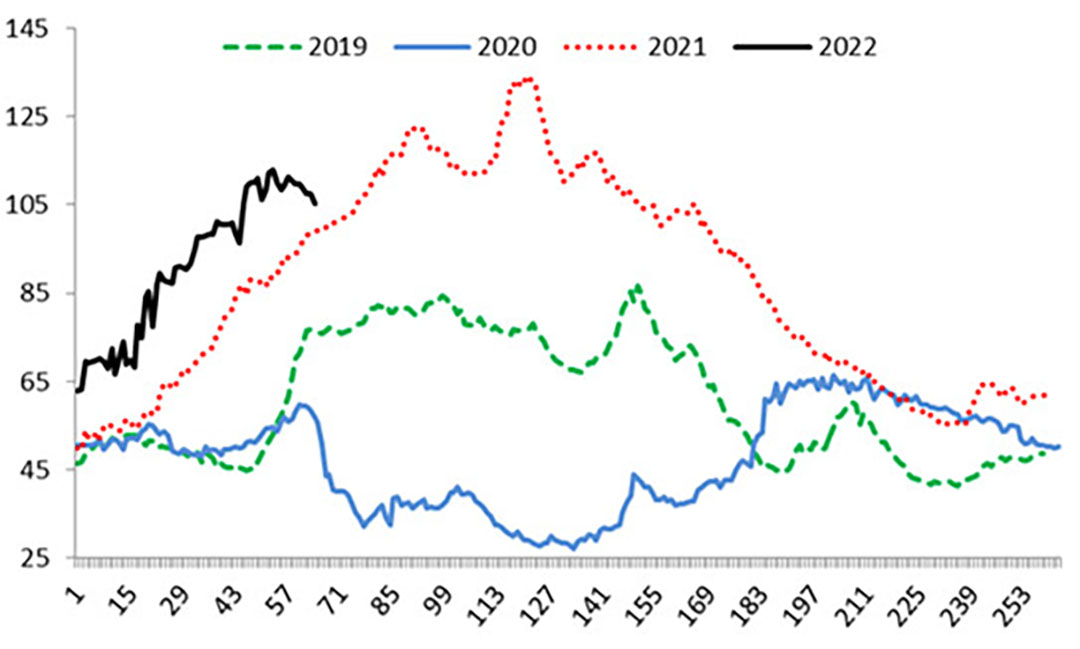

Figure 4 – US daily hog prices, 2019-2022, $/cwt dead weight.

Recovery in US hog prices

Figure 4 presents the daily hog price data in a year-by-year comparison in order to clarify the seasonal behaviour of prices. A recovery in US hog prices is observed in late 2021 and early 2022 and this is easy to understand on the basis of the census data. US hog and herd numbers have been declining consistently.

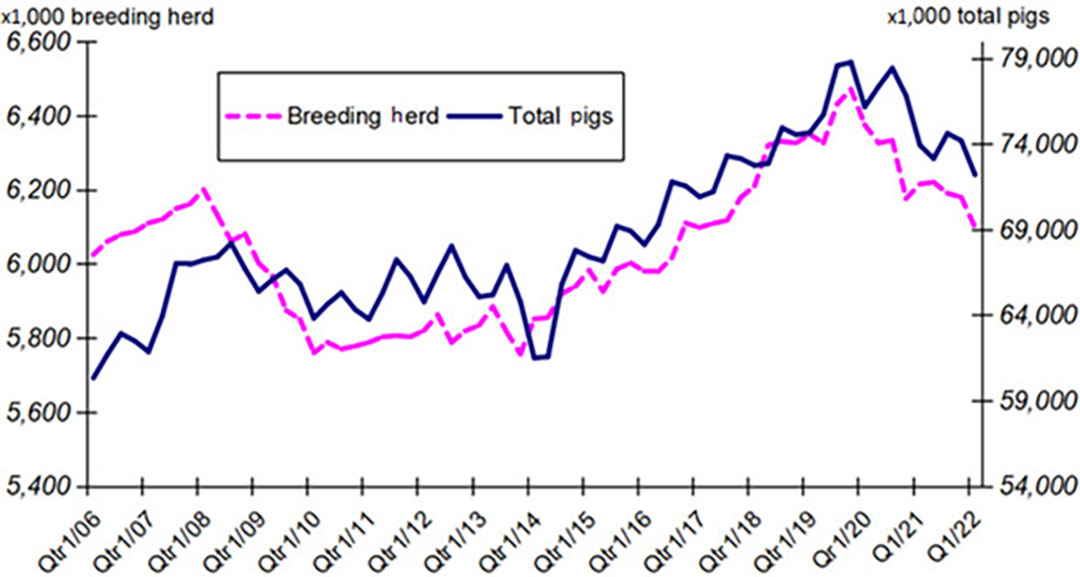

Figure 5 – US total pigs & breeding herd, 2006-March 2022.

Figure 5 shows these data in a chart going back to 2006. Table 1 presents the data from the latest (March 2022) USDA census. As reported by these data, the breeding herd in the United States is down by about 2% year on year. The census estimates for the total inventory shows a decline of about 1%.

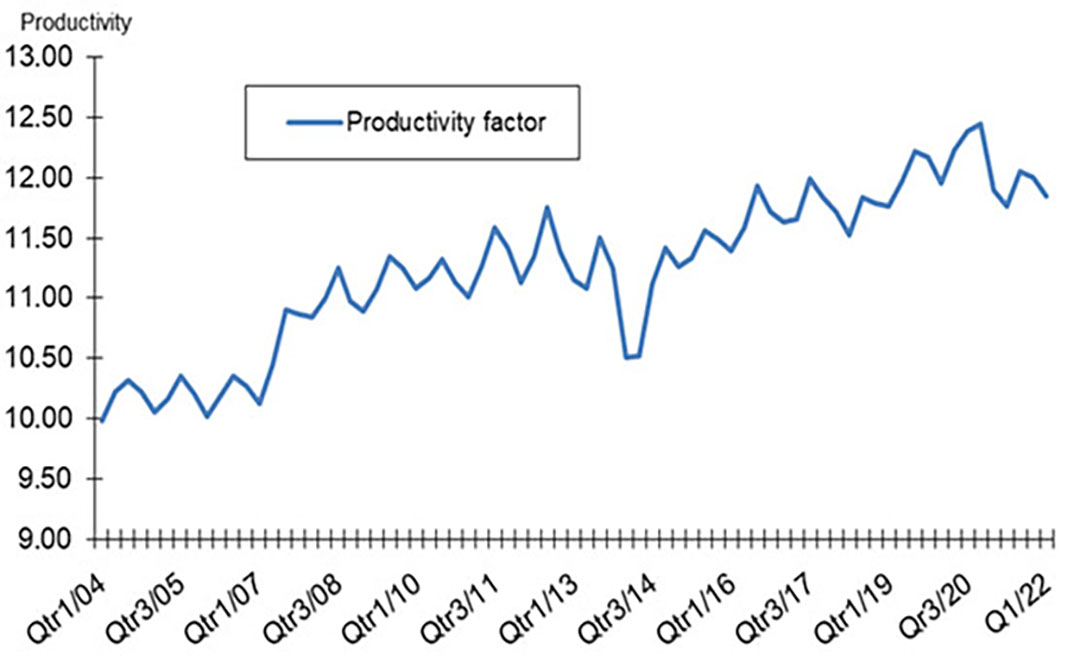

The estimate for the number of market pigs shows a fall of 3.5%. Figure 6 illustrates another aspect of the US pig sector’s performance – its productivity has been trending steadily upwards for several years but has declined recently. This may partly be Covid-related but it is more likely that a high incidence of Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) in sows is reducing on-farm productivity. The reductions in hog numbers reported by the recent USDA surveys along with the PRRS data, reinforce the view that US pork production will be lower in the first half of 2022.

Figure 6 – Productivity in US hog herds, 2004-March 2021.

Europe: Pig farmers in contraction mode

In Europe, pig farmers have been in “contraction mode” for almost all of 2021. The December 2021 census data for the EU indicated a decline 3.5% in the breeding herd. Only Spain, amongst the major pig producing countries, was expanding, with a herd increase of 2% at that date. Germany’s breeding herd was down 7%. The outlook for Europe’s pig numbers is negative in the first half of 2022 but, with rising feed and energy costs, I can’t see a rush to expand numbers and that suggests fewer pigs in the 2nd half of 2022 as well.

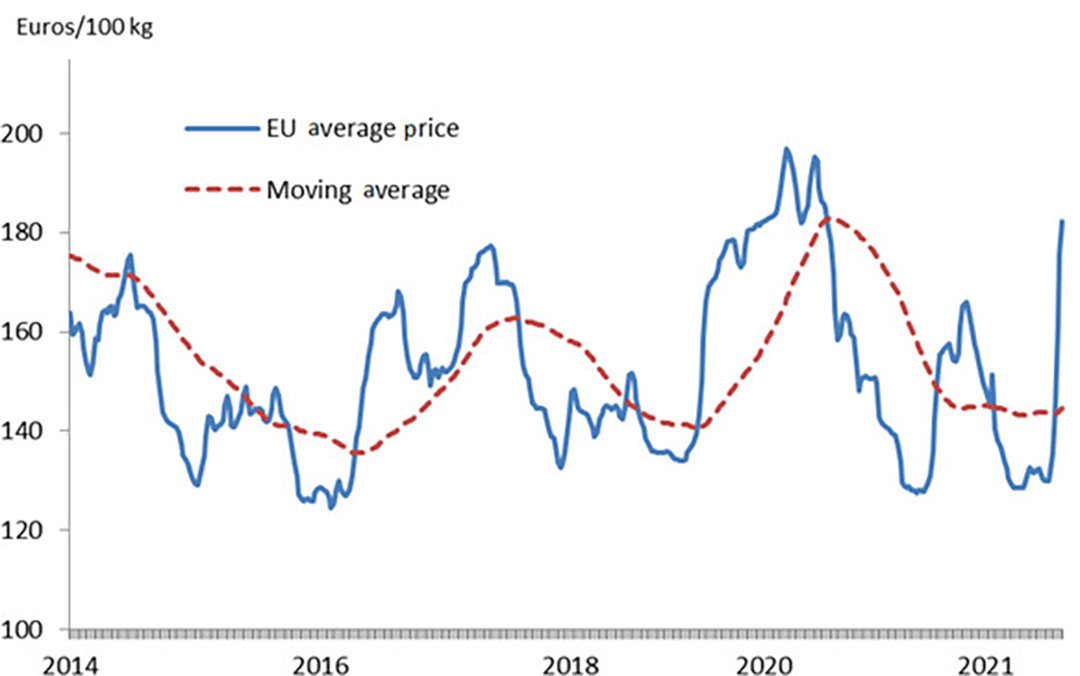

The sharp moves upwards in European pig prices shown Figure 7 indicates that the market is already short of pigs. EU pigmeat exports fell by 2.7% in 2021 but domestic demand seems to be holding up. So far, falling export demand (driven by China) has been countered by a recovering EU economy.

Figure 7 – EU pig prices (class E), January 2014-March 2022.

Resilience of the world economy

Now, what about the adjustment I mentioned earlier? How resilient is the world economy to the war in Ukraine, and the consequent sanctions on Russia? How will changes in production costs and consumer incomes affect market prices? And when will the phoney war end – when will these price changes be visible in the supermarkets?

Previous conflicts in the Middle East, Vietnam, Korea, Iraq and Afghanistan offer few clues. Although Ukraine ia not a big part of the global economy, Russia’s energy and commodity trade is significant, and has been brought into the mix. The economic impact is more akin to the Second World War rather than the regional “conflicts” we have seen since 1945. Last year, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had projected global growth for 2022 to be 4.4% but it will be publishing a revision to this after Easter and I expect that it will slash this forecast in half. I hope I am wrong.

Pig prices will be higher, so will costs

So, after viewing the text and charts above is it still a glass half full? I fear not, since the likely changes to producers’ costs and consumers’ incomes are just too great to allow the adjustment to be unnoticed in the shopping basket or in the production decisions on the farm and pig unit. Pig prices will be higher but so will costs, and consumer purchasing power in the supermarket will fall – and some consumers will go hungry in 2022.

This sounds more like a glass that is half empty. The one bright spot in this rather gloomy ending is that, if the war between Ukraine and Russia can be brought to an end in Ukraine’s favour there is likely to be a restructuring of the western economy and the Ukrainian agro-economy which will go some way to giving a boost to economic growth in western-aligned countries.

Beheer

Beheer

WP Admin

WP Admin  Bewerk bericht

Bewerk bericht