Back to the future for UK pig producers

Brexit, Covid-19 and new free trade agreements have not exactly made for heartwarming longer term prospects for the pig industry in the United Kingdom. In a way, the situation is much like it was in 2000 when stricter welfare rules were introduced, leaving the domestic market vulnerable to cheap imports. Will the same thing happen again?

The UK pig industry made headlines in the UK press in the autumn of 2021 – but for the wrong reasons. A shortage of workers in abattoirs and cutting rooms caused a drop in slaughtering capacity and a build-up of finished pigs on farms. It became bad enough that some farmers euthanised piglets and pigs on-farm – at least 20,000 pigs were put down and producers are still complaining about a backlog of pigs on farms as we enter 2022. Eventually, the British government agreed to a temporary increase in the visa allocation for non-British butchers and abattoir operatives. Nevertheless, pig prices, producer confidence and industry profits have suffered in late 2021 and early 2022. The question is, has all this been a minor bump on the post-Brexit, post-Covid road, or is this a turning point for the UK’s pig sector?

UK’s modest contribution to global exports

The UK pig industry is not a big player in the UK economy or trade statistics. It makes a modest contribution to the global export trade and the European market for pig meat. That said, there are some key products and primal cuts that it trades (or used to trade) with its EU neighbours. And the UK is an important source of cull sow carcasses to continental European buyers – albeit less so during lockdown.

On the demand side, the UK is a key export market for the Danes and the Irish. And the Netherlands, Spain and France all supply the UK market with finished products or with primal cuts that can be used in manufacturing processes to create finished products by UK firms. In aggregate, the UK is about 60% self-sufficient in pig meat, and this has been the case since the UK pig industry contracted sharply after the 1998–99 price crash and new animal welfare rules for the UK were introduced in 2000.

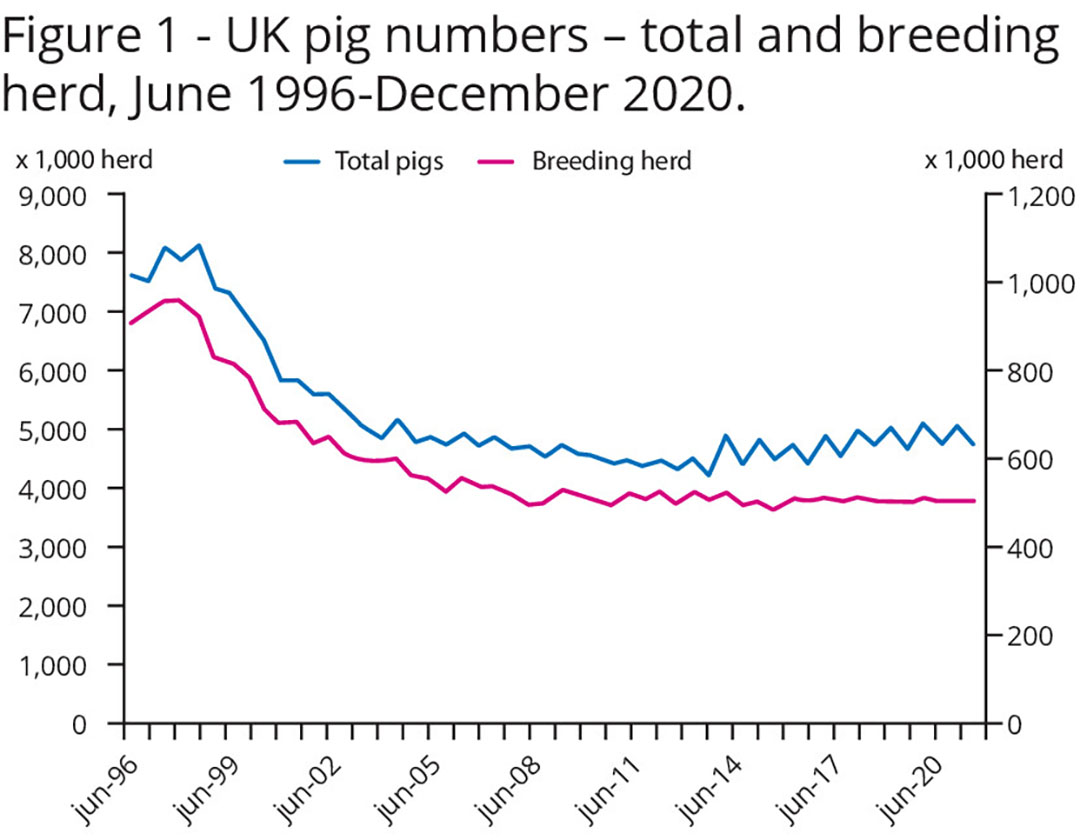

Figure 1 illustrates how the UK’s pig sector has shrunk in the last 20 years. British pig producers have not shown any inclination to get back to those early 2000 levels of pig numbers – it is fair to say that the industry was at equilibrium in the last decade. However, there are signs that the structure of production and trade, which has broadly been stable since about 2005, is about to change again.

The role of pig prices

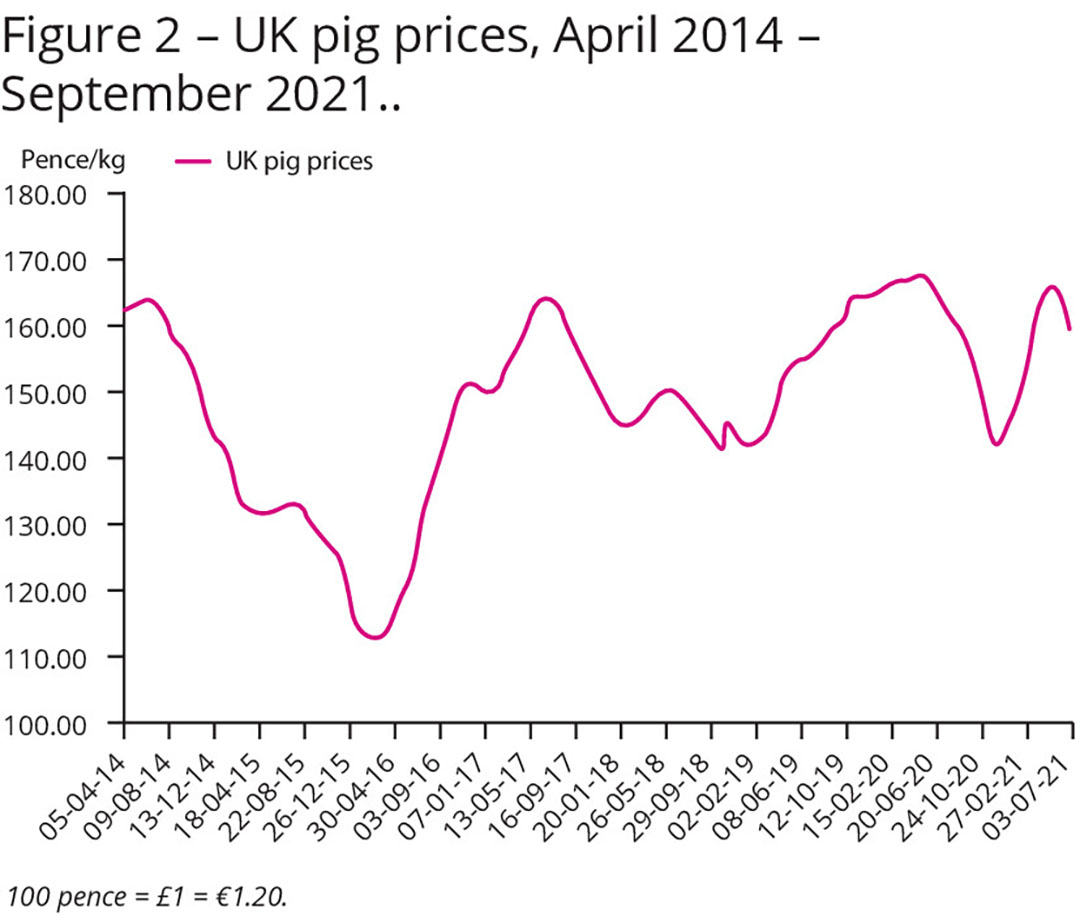

As ever, pig prices are part of the story. The UK’s experience of pig price volatility has, generally, mirrored the experience of its competitors in the EU. Figure 2 describes the UK pig price over a long period, and that does not look very different from the price behaviour of the EU’s average price. Despite this volatility and thanks to some hard work and investment by some producers, the UK’s pig sector has improved its productivity slightly (as measured by finished pigs produced from the national breeding herd).

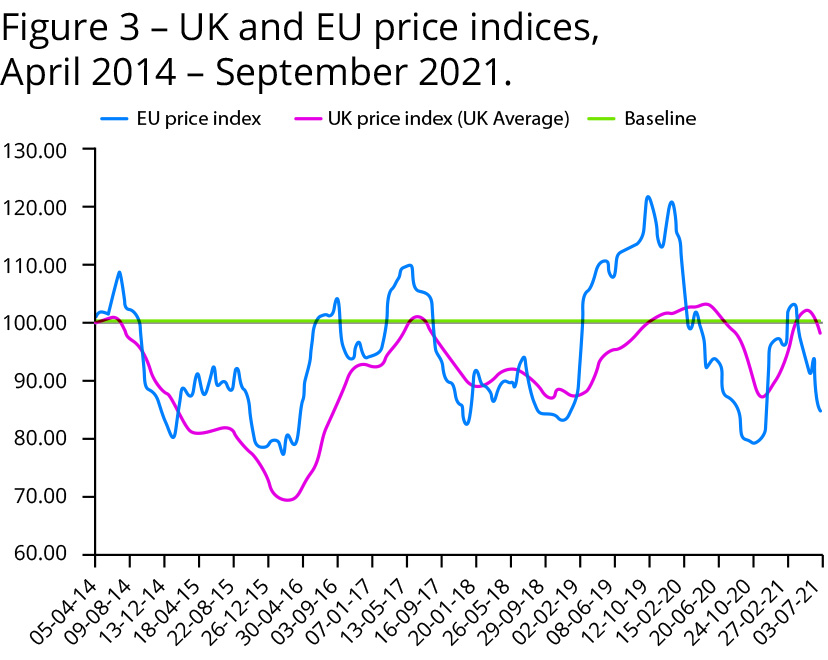

Some of the larger producers have also gained from longer term arrangements with processors, and some supermarkets have been more willing to stock British pig meat in preference to imports. All that is good news, but when comparing how UK and EU pig prices have moved over time, Figure 3 suggests that the EU’s producers have had a better experience. If UK and EU prices are indexed and charted against a base level (April 2014 = 100), price recoveries in the UK have been much weaker than those in the rest of the EU. The downswings in UK prices have mostly been as steep or steeper than those in the rest of the EU, and the upswings have been smaller and of shorter duration. The UK producer has had less opportunity to put on some “fat” when prices were relatively high – unlike the EU competition.

The obstacle called Brexit

If we leave aside the history, another obstacle to UK producers’ ambitions is now evident: Brexit. In itself, Brexit could have been a benefit to UK producers since the tariff arrangements under a no-deal Brexit with the EU favoured the UK’s domestic production. That would, however, have sharply increased consumer prices, and the UK Treasury and political class would never knowingly let that happen.

The Brexit free trade agreement deal with the EU swept those tariffs away leaving only non-tariff barriers (sanitary and phytosanitary issues – SPS) to be resolved. Mysteriously, the UK government has steadfastly refused to introduce SPS checks on meat imports from the EU – while the EU, to protect its acquis, has enforced SPS checks on imports. The UK has requested that full import certification and checks on goods coming into the UK from the EU are postponed until July 2022. In effect, pig meat exported to the EU from the UK has to meet all human and animal health standards – with full documentary evidence required and inspection at the border for each shipment.

But pig meat travelling from the EU into the UK is not subject to inspection until mid-2022. In 2021, when Covid-19 issues were less onerous for demand, UK exports were down by about 40%, whereas the UK’s imports from the EU were down by about 10% (see Table 1). Most significantly, and noticed by the mainstream media in the UK for various sectors, the post-Brexit visa arrangements for immigration in the UK along with Covid-19 lockdown policies have combined to ensure that there are major labour shortages in different parts of the UK economy. Line workers in UK abattoirs and butchers in cutting rooms are categories of immigrant workers who could not get visas.

Easy remedies by the UK government

Faced with this situation it might seem that the UK government had some easy remedies (e.g. short-term increases in visa numbers or relaxation of visa requirements) but the reaction of the ruling party in the UK, even to the sight of healthy pigs being culled on-farm, was muted and only after weeks of pressure and a potential animal welfare scandal were 800 extra visas granted for pork butchers.

2 other aspects of UK trade policy are worth a mention at this point – the bilateral trade deals agreed with Australia and New Zealand. These deals have yet to be published in full and ratified, but it is clear that both of them will increase access to the UK for supplies of beef and lamb from those countries. As the British Meat Processors Association in the UK correctly observes, it is not the volume of access that can damage UK producers, but the timing and value of the cuts of meat that are imported.

Future of the pig industry in the UK

What does the row about visas for pork butchers and these new trade deals tell us about the future of the pig industry in the UK? It would appear that there is an ideological position being taken by the UK government that, if carried though into policy, will change the fundamental arithmetic of the UK pig sector (and the farming sector in general). The UK government has not made it easy for the pig industry to adapt to Brexit-linked skill shortages and it must know that, for some sectors, this means losses and a cutback on production. At the same time the government will know that consumers require food on supermarket shelves. Making it easy for importers (no SPS checks for EU-sourced pig meat) and increasing access to new sources of meat supplies (Australia and New Zealand) address this issue by allowing imports more or easier access to the UK.

No barriers to less welfare-friendly imports

Indeed, this policy has been seen before, and that is why this article is titled “Back to the future”. When stricter animal welfare rules were introduced in the UK in 2000 there were no barriers to less welfare-friendly imports from abroad. In effect, the UK consumer avoided the price of higher welfare in the UK by buying imported pig meat. And now, the UK will avoid having more immigrants by, in effect, buying imported pork produced by those same workers – but they will be based and employed overseas. When the UK’s negotiators get around to agreeing trade deals with major pig meat exporters like Canada, Brazil or the USA, the UK’s pig industry should now know what to expect.

It is back to the future for the UK pig sector.

Beheer

Beheer

WP Admin

WP Admin  Bewerk bericht

Bewerk bericht