Impact of ASF on Asia’s wild boar population

Perhaps it is stating the obvious, but – as in Europe – wild boar and native pig populations in Asia have been strongly affected by the emergence of African Swine Fever. As all the attention and resources in Asia were directed to the virus’ effect on domestic pigs, the impact on Asia’s wild boar population remained under-reported for a long time. Data from peninsular Malaysia make those effects tangible – thus confirming a new, permanent pig health reality in Asia.

There has been little reporting on the extent of African Swine Fever (ASF) in wild boar (Sus scrofa) from Thailand, peninsular Malaysia, Singapore and Sumatra, where the species is abundant – or hyperabundant – across much of the region’s intact and degraded forests, including logged, fragmented and edge habitats. The lack of documented ASF in South East Asia’s wild boars to date has been perplexing given their prior high densities, gregarious social behaviour and propensity to utilise human-modified landscapes, increasing their proximity to domestic pigs that are ASF vectors.

Wild boar in Malaysia

An international team of researchers has been monitoring the population of native wild boar at the 130 km2 Pasoh Research Forest in peninsular Malaysia for 3 decades. Pasoh is home to Asia’s longest running permanently staffed forest dynamics plot, providing the opportunity to monitor the ASF outbreak. The population dynamics of Pasoh’s wild boar are closely tied to cross-boundary food subsidies provided by oil palm fruits in plantations that are adjacent to the reserve.

Before the incidence of ASF, Pasoh’s wild boar densities were estimated at 27–47 individuals/km2. Those densities are higher than wild boar densities in natural forests without external food subsidies (2–10 individuals/km2) and have therefore been referred to as “hyperabundant”. Pasoh’s wild boar population declined when adjacent oil palm trees were not fruiting from 2002 to 2006. However, carcasses were not found during these non-fruiting periods, suggesting that the wild boar migrated from the area and did not die in large numbers from starvation. When the neighbouring plantations resumed fruiting in 2007, the wild boar population increased exponentially until 2012 and remained hyperabundant through to February 2022.

The team examined the mortality dynamics of an ASF outbreak in Asian wild pig species and made pre-ASF and post-ASF comparisons by repeating the same wildlife sampling approaches (transects and camera trapping) previously employed at the site from 2013 to 2019.

Study site

The Pasoh landscape is one of the flagship sites for permanent ecological monitoring by the Smithsonian Institution. Pasoh is home to a 50 ha forest dynamics plot censused every 5 years since 1986 and has had weekly phenology monitoring since 2003; annual wildlife surveys including camera trap surveys since 2013; hunting assessments since 2014; and experiments that link dynamics of humans, wildlife and plants ongoing since 1996. The habitat is primary and selectively logged lowland rainforest. There is a diverse wildlife community with an elevated population of wild boar that consume nearby oil palm fruits, but bearded pigs (S. barbatus) have been absent from the landscape for 2 decades.

The arrival of ASF and wild boar carcasses

A team from the Forest Research Institute of Malaysia (FRIM) monitored the presence of wild boar and carcasses from March to July 2022. The team estimated the time since death for all carcasses based on decay rates that have been previously studied at the site. Wild boar carcass decomposition in Malaysia shows little bloating and minor smell in the first 24 hours, bloating and minimal smell in days 2–4 and obvious flesh decay and a putrid stench in days 4–12 days, leaving dry remains of skin and bone after just 12–16 days. From 16 to 30 days, carcasses can still be identified by the lingering stench, enormous numbers of flies and larvae on the soil, and distinctive bones and skulls.

Camera trapping

The research team conducted systematic camera trapping annually from 2013 to 2018 (pre-ASF) and again in 2022 (post-ASF). Cameras were deployed for about 30 days in 2013–2016 and in 2018; they were deployed year-round in 2017; and the post-ASF survey was 58 days in June–August 2022. The team considered captures independent if they occurred at least 30 minutes apart.

The arrival of ASF

Mortality of a forest-dwelling wild boar from ASF was confirmed at the Pasoh Research Forest on 10 February 2022 using PCR testing. During February, March and April of 2022, there were occasional unusual observations of rotting wild boar carcasses and the associated stench. By 9 May, the team observed a wild boar mass mortality event in full swing, repeatedly encountering carcasses and the stench of rotting carcasses when entering the forest. The peak frequency of encountering carcasses occurred from 15 May to 7 June and then declined and became rare by 15 July 2022.

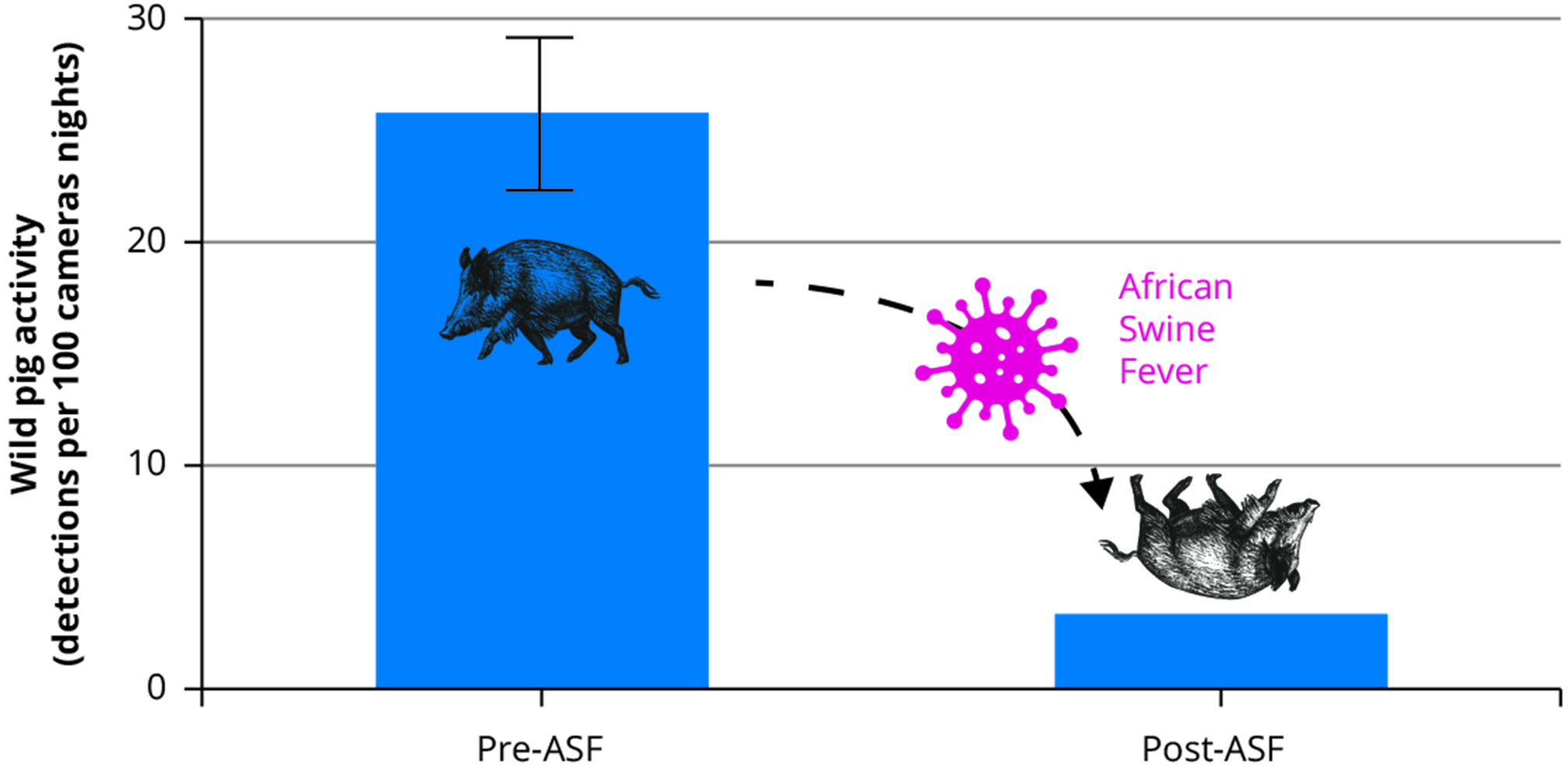

Wild boar activity in camera trapping

Camera-trap observations of wild boar activity at the site revealed an 87% decline in capture rates in 2022 compared to average levels from five prior surveys spanning 2013–2017. Specifically, the relative activity index (RAI; independent captures per 100 trap nights) averaged 25.56 from 2013 to 2017 and was just 3.39 in 2022. The only scavenging activity observed on cameras was a sun bear eating maggots from a carcass during its advanced decomposition stage.

Mortality increase

The research team observed an increase in wild boar mortality by about 100-fold in June 2022 compared to prior years that coincided with the initial onslaught of ASF in peninsular Malaysia. After a few cases in February, the virus appears to have been widely transmitted in April 2022. Following a 1-week to 3-week incubation period, most mortality occurred within a 3-week period from mid-May to early June, which was corroborated by both the onsite FRIM staff and verified by the decomposition states of carcasses observed in early June. Live wild boar activity measured with camera traps declined dramatically by 87% suggesting that ASF killed the majority of the wild boars previously living at the site.

Wild boar sought existing birthing nests as locations to die (“funeral nests”), which is the first known observation of this behaviour to our knowledge. The use of funeral nests may be perceived as safe places during vulnerable periods, similar to their motivation during birthing. The research team could not determine the sex of animals using funeral nests, but it is possible that the same sows that built nests for birthing also used them to die.

Wild boar carcasses appear to be in advanced decay within 2 to 3 weeks suggesting detecting ASF outbreaks requires timely surveillance in rainforest conditions and may have been missed in other locations, and that the carcass meat resource subsidy provided to predators and scavengers is extremely ephemeral.

Consequences for Asia

Apart from unexpected effects on plant and other animal populations, the cascading impacts of declining wild pigs in South East Asia will also affect human economies and livelihoods. Wild pigs are important species for some indigenous cultures in South East Asia, especially in Borneo and New Guinea where they play a central role in ancient hunting traditions, modern economies and customary gift-giving and dowries. As ASF eliminates options for sustainable pig hunting and husbandry, compensatory hunting targeting more endangered, rarer and slower reproducing wildlife may spell a conservation disaster. The loss in nutritional and cultural terms is likely to acutely impact the region’s indigenous peoples.

ASF is likely to stay in Asia, similar to in Europe. As a result, “backyard pig farming” – once common in Asia – is no longer sustainable. More commercial domestic pig operations will require dramatically higher biosecurity, and this will incur associated costs, infrastructure, and training and capacity building.

This is an edited, abridged and approved summary of a scientific article called “The mass mortality of Asia’s native pigs induced by African Swine Fever,” published in Wildlife Letters in April 2023. Apart from author Matthew S. Luskin, the text was co-authored by Jonathan H. Moore, Southern University of Science and Technology, China and University of East Anglia, UK; Calebe P. Mendes, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore; Musalmah Bt Nasardin, FRIM, Malaysia; Manabu Onuma, National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan; and Stuart J. Davies, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, USA.

Beheer

Beheer

WP Admin

WP Admin  Bewerk bericht

Bewerk bericht