Better sow performance starts with good prevention

As indicated by earlier articles, sow lameness is a major reason for decreased sow longevity in swine breeding herds. The cost of lameness is estimated at €140 per case or €20,000 annually for a herd with 1,000 sows assuming 15% of the sows are lame at any one time throughout the year. A lifelong attention to the sow’s physiology can help – this already starts with paying extra attention to young gilts.

By Dr Christof Rapp, Zinpro Animal Nutrition, Boxmeer, the Netherlands

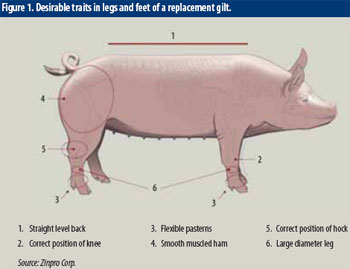

Lameness can be caused by many factors such as housing, nutrition, stockmanship, genetics and gilt rearing and nutrition. The latter is an area that is still neglected in many operations primarily because of a lack of awareness of what impact management and nutrition during gilt rearing can have on longevity of sows. Ideally, an incoming gilt into a herd needs a variety of different traits, as can be seen in Figure 1. This article will discuss the causes of why pigs go lame and measures to prevent and control swine lameness, which ultimately increase sow longevity, with a focus on gilt rearing.

Claw lesions are very prevalent in sows and are often the reason for lameness. Up to 50% of the sows that are culled due to feet and leg problems are first-parity sows. Claw lesions increase as the pig gets older. As of today we do not know how prevalent lesions in rearing gilts are. However, in a case study moderate and severe white line lesions and heel overgrowth and erosion were found in a significant proportion of rear feet from gilts at seven months of age (Figure 2). To ensure a long productive life of the sow it is important that incoming gilts have claws with no or little lesions. Gilts with severe claw lesions should be culled.

Overgrown heels are the most common disorder of the claw. This condition is triggered by standing and walking on a hard surface such as concrete floors to which gilts and sows are typically exposed day in day out. While heel overgrowth is a callus in the first place that does not cause pain as such, it puts considerable pressure on the side wall and white line, which in turn may cause lesions in the latter areas of the claw. Heel lesions, side wall cracks and white line have been reported to be associated with lameness. Not every lesion causes lameness. Lesions that reach into the living tissue (corium) cause pain which then makes the gilt go lame. The feet of gilts should be evaluated for claw lesions during the selection process. Small shallow lesions are tolerable but gilts with severe lesions should be culled.

Controlling long toes

Long toes are one of the most visible claw disorders in sows. Gilts with long toes bear more weight on the heels which then leads to more claw lesions, increasing the risk for lameness. While gilts typically do not have severely overgrown toes, some gilts may have toes within the same foot that differ substantially in length.

Because a difference of more than 1.2 cm is a heritable trait, selection of gilts for equal toe length helps to control long toes. Another reason for overgrown claws seems to be insufficient wear of toes due to prolonged time spent on plastic slats during the early rearing phase. It is therefore recommended that gilts be moved off plastic floor onto a concrete floor, which provides more wear of claw horn, once they have reached 25 kg body weight. Gilts with long toes should be culled.

Sound leg structure

It has been known for a long time that good leg soundness and leg structure of gilts are critical to ensure long productive lives of sows. Thus besides inspecting claws for lesions, legs should be evaluated in terms of leg angle, foot position and front and rear alignment (Figure 3). Gilts with unfavourable leg traits should be culled.

Moderate body weight gain

Leg weakness is increased and longevity is decreased in over-fed gilts. To ensure long productive lives as sows, gilts should gain body weight at an average rate of 700 g/ day between ten and 30 weeks of age. This means that feed intake needs to be restricted. Grower and finisher swine diets are formulated to maximise growth rate and do not meet the specific nutritional needs of gilts and thus are not suitable for gilts. In the rearing period the ideal number is six but no more than ten gilts per pen. This is critical to make sure that variation in body condition between gilts is minimised.

Flooring and fighting

Flooring is the most critical factor to ensure good foot health. Slats with sharp edges or broken slats increase the risk for traumatic injuries such as heel cracks and side wall cracks. Wet floors are also associated with an increase in claw lesions. The obvious reason is that a wet floor provides less traction and claws get damaged as the gilt slips. If floors also have manure built up in addition to high moisture, the quality of claw horn is deteriorated. As moisture increases so does ammonia release. Ammonia decreases hardness and elasticity of keratin, the main component of claw horn. This facilitates keratin breakdown through enzymes produced by bacteria.

Fighting of swine also increases the risk for claw damage. White line lesions are more prevalent in herds with loose-housing of sows during gestation. Providing good flooring and minimising fighting of gilts during rearing are critical for decreasing lameness and increasing longevity in the breeding sow herd.

More floor space for gilts

In humans it is known that exercise has a positive effect on proper development and maintenance of the skeleton. Swine are not any different in that respect. Gilts need enough floor space for proper development of skeleton and muscles. This is in particular true for gilts that go into herds with loose-housing of gestating sows.

Researchers from Wageningen University & Research Centre in the Netherlands recommend 1-2 m2 of floor space per gilt from 23 kg bodyweight onwards. The relation between floor space during rearing and removal rate of first and second parity sows was investigated by the same researchers in a survey of 70 Dutch sow herds with loose-housing of sows during gestation. It was found that farms that provided 1.9 m2 floor space per gilt in the pen prior to insemination removed less than 5% of first and second parity sows whereas herds that provided only 1.3 m2 floor space per gilt removed 10% and more sows after the first and second parity (Table 1).

Exercise and training

Herds with loose-housing of sows during gestation should train gilts during the rearing period to use the feeding system for gestating sows. This is particularly important when electronic sow feeders are being used in the gestation period.

Gilts should share a common pen with older sows before they are included in the sow breeding herd. This helps gilts to acquire social skills so that a hierarchy among sows and gilts can be established without too much fighting.

In conclusion, stringent selection of gilts for sound leg structure and healthy feet and controlling risk factors for lameness during the rearing phase decrease lameness and sow removal. Good management and balanced nutrition of developing gilts provide a large opportunity to improve profitability of swine breeding herds.

| Improved nutrition – better claws The major constituent of claw horn is a structural protein called keratin. Formation of keratin requires a number of nutrients including protein, macro minerals, vitamins and trace minerals such as zinc and copper. It has been reported that horn formation in the heel, white line and coronary band areas are very susceptible to a lack of nutrient supply. Interestingly, lesions are most frequently found in the heel area and, if sows are housed in groups during gestation, also in the white line. Recent research in sows has shown a significant decrease in number and severity of total claw lesions (14%), a drop in lameness (16%) and faster healing of cracks in the heel and side wall when a portion of inorganic dietary trace minerals (sulfates) were replaced with an organic source (Availa Sow, Zinpro Performance Minerals). Because preventing and healing of lesions in gilts is equally if not more important than in sows, gilts’ diets should be formulated to optimise foot health. Feeding balanced diets to gilts specifically formulated for gilts are crucial to help increase longevity of sows. |

For more information, visit the Feet First Symposium report at: www.pigprogress.net/photo-gallery

Beheer

Beheer

WP Admin

WP Admin  Bewerk bericht

Bewerk bericht