3 Steps to fight post-weaning diarrhoea

It is well-known that post-weaning diarrhoea in piglets is a multifactorial problem. Tackling that without the use of antibiotics or zinc oxide requires a multifactorial solution as well. Here are a few: the use of undigestible fibre in feed, the use of inflammation biomarkers and adhering to a total health plan.

In recent years, producing without antibiotics has become one of the major issues in the pig business. Pressure from local and international organisations as well as consumer demand are leading to companies setting up entirely new production chains. Now the challenge is to extend that concept to pig farms. For swine farms to be able to produce without antibiotics, one of the main challenges is the problem of post-weaning diarrhoea.

Using undigestible fibre in feed

Using undigestible fibre in feed

Digestive disorders during the first week post-weaning are often associated with feed consumption. The time between weaning and the first intake can be up to 2 days, leading to a lower digestive capacity. It is very important to limit bulimia, which could be provoked by hunger. In that context, the use of undigestible fibre in feed can help.

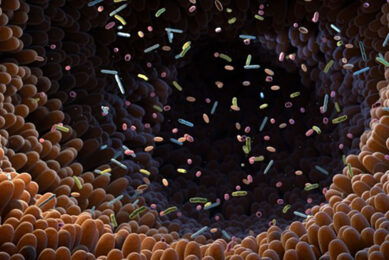

Because daily feed intake is usually divided into meals of different sizes and patterns, digestion processes adapt to those situations: feed is retained in the stomach, and small quantities of feed are released intermittently into the small intestine. Muscle contractions help the feed to move through the intestine to reach the colon. In that process, a key role is played by the ileo-caecal valve (or sphincter), which limits bacteria-rich refluxes from the large intestine back into the ileum (see Figure 1). Digesta are fermented and discharged regularly at the rectum and excreted.

Figure 1 – Drawing of an ileo-caecal valve.

After weaning, however, the digestive capacity is very limited because of low stomach acidification and because of the transient reduction of hydrolytic and absorbing surface of the small intestine. Immaturity of the piglet’s digestive tract at weaning therefore does not allow correct sphincter function between the caecum (where bacteria live) and the ileum. When refluxes from the caecum or colon to the ileum occur, the presence of bacteria in the ileum increases the risk of contamination by opportunistic pathogens (e.g. coliforms) and, consequently, the risk of digestive disorders.

Adding feed structures can strengthen the sphincter. In 2015, a team led by researcher Maria Grazia Cappai at the University of Sassari, Italy, showed that increasing the fraction in feed of particles greater than 1mm enlarged the thickness of the ileo-caecal valve, resulting in lower presence of opportunistic bacteria in ileum.

In addition, indigestible fibre can limit the adhesion of E. coli to the intestinal mucosa and consequently decrease the incidence of piglet diarrhoea. More regular meal patterns facilitate the transit, limiting the accumulation of non-digestible materials in the hindgut and consequently the amount of nutrients available to gut bacteria.

Those properties were verified in a trial conducted at the Mixscience research facility. In that trial, the results of 3 groups of piglets were compared. The piglets received a pre-starter feed containing one of the following:

- 0.61% lignin

- 1.53% lignin

- 2.45% lignin.

In the group receiving the highest level of lignin, no piglet needed to be treated against diarrhoea. The growth difference between pigs treated or not for diarrhoea was higher in the group receiving the lowest level of lignin (0.61%) than in the group receiving 1.53% lignin. Piglets fed with the highest level of lignin increased feed intake by 16%, whereas growth rate grew by 27% compared to those receiving the lowest lignin level. Piglets with higher lignin content were also significantly cleaner than other piglets (when measured in manure marks on the body).

Limiting intestinal inflammation

Limiting intestinal inflammation is also an important way to control intestinal health. A faecal biomarker to quantify intestinal inflammation can be used to study effects of weaning feeds. Myeloperoxidase (MPO), a biomarker of neutrophil activity, is a component of lysosome. When those immune cells accumulate and degranulate in the intestinal mucosa, MPO is released into the gut lumen. The enzyme has been used in human medicine for decades to confirm diagnostics of inflammatory digestive diseases, and it is stable on microbial degradation in the colon.

A presentation at the Zero Zinc Summit in June 2019 in Copenhagen, Denmark, concluded that faecal MPO was not influenced by sex or weaning weight of piglets. That research was based on 292 individual samples. However, faecal MPO was influenced by the piglet’s age at sampling and the faecal mark according to the Bristol stool scale. The MPO increased with poor faecal condition. In combination with zootechnical performance, that analysis enables suitable recipes for feed to be designed without antibiotics or zinc oxide.

3. Applying an overall concept

In digestive health, feed plays a central role. It cannot, however, be the only way of fixing problems on-farm. Nutrition should therefore be integrated into an overall concept including building, genetics, farm management, the producer’s information level, water, pathogen pressure and a veterinary prophylaxis plan. At Mixscience, such a strategy is known as the Sustainable Animal Health Management approach.

This approach is illustrated by a study carried out in 2019 in the company’s research facilities which compared sanitary and zootechnical performance of piglets housed in an old building (older than 30 years) with poor ventilation and concrete slatted floors against those in a fairly new building with a steel floor. Among piglets housed in the older building, 44% were treated for watery diarrhoea, compared to 2% in the other building (see Figure 2). The diarrhoea was associated with a decrease in feed intake of 8% and weight gain reduction of 20% over the first 21 days after weaning.

References available on request.

Beheer

Beheer

WP Admin

WP Admin  Bewerk bericht

Bewerk bericht