When is an enzyme in feed, not a feed enzyme?

Feed enzymes increase the nutritional value of poultry feed, but other kinds of enzymes can be used to improve gut health. Bacterial peptidoglycans negatively affect gut function – these enzymes help break them down, increasing production efficiency.

The practise of adding enzymes to poultry feed is virtually an industry standard. Phytases, carbohydrases, lipases and proteases – as well as increasing the nutritional value of feed – help prevent the negative effects of anti-nutritional factors in raw materials.

Enzymes for feed

Phytases are enzymes that enhance the release of phosphorus and trace minerals from plant phytate. Carbohydrases – like xylanases, gluconases, furanosidases – degrade non-starch polysaccharides, allowing the animals to obtain more energy and/or nutrients from their diet. Proteases and lipases on the other hand, support and reinforce the action of the bird’s own digestive enzymes to break-down protein and fat.

Figure 1 – PGN is present in the cell walls of both Gram- and Gram+ bacteria.

Protection mechanisms in the gut

Bacterial cells are protected by several layers including; membranes, lipopolysaccharides, proteins and peptidoglycans (PGN). Gram-positive bacteria have a thick outer layer of PGN, whilst gram-negative bacteria have a thinner PGN layer in between the inner and outer membrane that is covered by lipopolysaccharides (Figure 1). In a healthy gut, tight junctions are maintained, and pathogens can’t move through the gut barrier. But in commercial broiler production, damage to the intestine is inevitable. Bacterial cell wall fragments present in the gut, including PGN, can impact nutrient digestion and absorption. This is due to intestinal inflammation reactions PGN may trigger by binding to the epithelial receptor TLR2. Even animals in the best of health always have some inflammation in their gut. If it needs to be increased in response to a threat from pathogens, it is easier to do so from that position (e.g. – scouring and vomiting to quickly expel pathogens).

Poultry’s relationship with bacteria.

All animals are taking in microbes constantly from their food and the environment – the gastrointestinal tract has evolved to cope with this normal threat. The acidic environment of the stomach kills certain bacteria, whilst putting others into a dormant state where they are no longer metabolically active. This means that they can no longer take up nutrients intended for the host animal. They pass to the small intestine, where the nutrients from the feed can be absorbed by the bird. Here the flow of digesta is relatively fast to prevent recovery of the bacteria before they reach the large intestine.

Once in the caeca, in the case of birds, the bacteria recover. In fact, the environment supports them to do so, creating a symbiosis between microbes and host. Here they multiply and feed on the indigestible parts of plant cell wall, such as polysaccharides. In return animals can take advantage of the nutrients bacteria produce; including B vitamins and short chain fatty acids like butyrate and propionate.

Enzymes for gut health

Enzymes produced in response to infection are the cornerstones of innate immunity. They can help to modulate the host’s immune system when pathogens are present, with some having an antibacterial effect. In the gut, PGN recognition proteins bind to PGN and are able to cleave the molecule into smaller pieces. For example, lysozyme is an endogenous enzyme that can break down PGN, hydrolysing the cell wall of the bacteria and killing it. But a bird with a high feed intake like a broiler cannot make enough lysozyme to breakdown the amount of PGN present in its gut. Muramidases are enzymes that can breakdown PGN, forming muramyldipeptide (MDP). It does this by breaking the bond between the 2 sugars that make up the backbone of peptidoglycan.

Inflammatory effects

If severe inflammation occurs in the gut it has a negative effect on animal performance, because it tells the gut to stop absorbing nutrients – making more nutrients available to bacteria. If nutrients aren’t absorbed in the small intestine, they pass into the large intestine, feeding bacteria instead of the animal, a process that favours pathogenic bacteria (like Salmonella). There is a double negative effect – nutrients are not available for growth but instead cause an unfavourable shift in the microflora of the caeca.

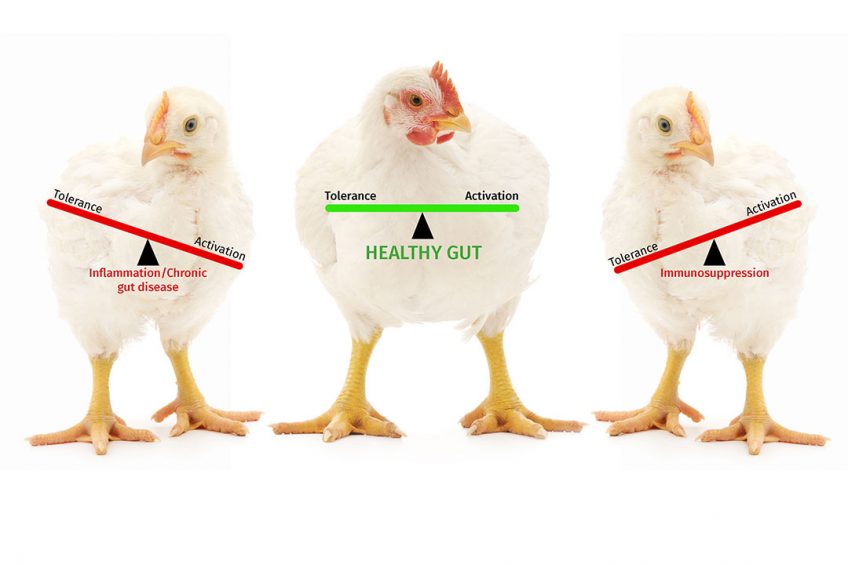

The opposite side of the ‘scales’ are NOD2 sensors that are involved in barrier protection and surveillance at the cell wall. MDP, released from the total breakdown of PGN is taken up by epithelial cells. This activates NOD2 to tell the body that the threat is passed, and it is safe to start absorbing nutrients again. This negative feedback loop has anti-inflammatory action.

Exploiting the mechanisms

If synthetic muramidase* is added to the feed, more PGN is broken down; resulting in a balance between anti- and pro-inflammatory responses. However, it is impossible to break down all the PGN in an animal’s gut. In fact, it would not be beneficial to do so as TLR-2 responses are essential to animals’ immunity. Instead it is the tight junctions that should be maintained in order to stop PGN reaching the receptors. The release of MDP has a direct effect in the small intestine by continuously activating NOD2 receptors – it switches off inflammation and switches back on nutrient absorption. So that the bird is getting all the nutrients it needs for optimal performance.

Achieving a balance

Bacteria are everywhere, they co-evolved with us and we can’t escape them. This means that the risk of PGN to intestinal health and optimum production is constant. Under commercial conditions animals do not have sufficient endogenous enzymes to breakdown PGN effectively. Supplementing with gut health enzymes such as muramidases, optimises this process and by acting only on dead bacteria supports a beneficial microbiome. The MDP released switches the animal from inflammation to the healthy situation of optimum nutrient absorption; avoiding an excessive immune response that has a negative effect on animal performance.

This novel enzyme category has a completely different, but complementary, mode of action to traditional feed enzymes. They can work together with traditional feed enzymes to improve the sustainability of animal production. The answer to the riddle posed in the title is that whilst feed enzymes hydrolyse nutrients to improve what is available for the bird. Gut health enzymes help to break down an inevitable waste product – PGN – and in so doing improve the efficiency of the bird’s digestive and immune systems.

*Balancius from DSM

References available on request

Author:

Prof. Dr Richard Ducatelle, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Pathology, Bacteriology and Poultry diseases, Ghent University

Beheer

Beheer

WP Admin

WP Admin  Bewerk bericht

Bewerk bericht